The Phillips Curve

Inflation, unemployment, and deciding between them

Yesterday’s monthly job report was nothing short of encouraging, with unemployment falling to 3.5% (vs the expected 3.6%) and 236,000 jobs being created. What’s most curious about these numbers is that they show just how resilient the US labor market is to tightening monetary conditions. In the Fed’s attempt to clamp down on aggregate demand and restrain inflation, unemployment continues to decrease. This leads us to an interesting question that economists have wrestled with for decades: how does the inflation-unemployment linkage work?

The origins of the Phillips curve

A 1958 paper entitled “The Relation Between Unemployment and the Rate of Change of Money Wage Rates in the United Kingdom, 1861–1957” is generally thought of to be the first adaptation of the Phillips curve. The author, A. William Phillips, documented the relationship between the UK unemployment rate and the rate of change of nominal wage rates and found a positive correlation between unemployment and wage rates (technically Irving Fisher also noted this correlation in the 1920s, but he didn’t focus on nominal wages the way Phillips did). This suggests that higher unemployment coincides with slower wage growth, an observation that Phillips attributed to workers being more willing to accept lower wages during periods of high unemployment.

If jobs are hard to come by to begin with, chances are people will settle for lower pay if it means securing employment. The main policy prescription that Phillips took away from this? If you want to support long-run wage growth, focus on reducing unemployment.

Since then, economists have studied and argued over this simple idea of unemployment and inflation (which, in the original diagram, is reflected in wage growth), creating a stark divide between Keynesians (who favored the Phillips curve in policy-making) and monetarists (who were skeptical of its utility in policy). The real turning point, however, arose during the 1970s.

As noted in our stagflation article, the United States experienced both high unemployment and high inflation during this era, a phenomenon that the Phillips curve (which, in this case, posited that unemployment would fall as inflation grew) couldn’t explain. Monetarists pointed to this as an example of the Phillips curve’s unreliability in explaining inflation-unemployment dynamics. This created an important distinction between the long and short-run Phillips curve (LRPC and SRPC, respectively). Most economists agree on the SRPC’s usefulness, but there still exists controversy over the LRPC (we’ll get to this shortly).

The Phillips curve model

So why does the inverse relationship between inflation and unemployment exist to begin with? The answer can actually just be reasoned through like so:

An economy with low unemployment implies a high utilization of labor market, that is, not a lot of people actively looking for jobs

As such, workers have more bargaining power because there are fewer available workers in the labor market, meaning employers must compete to attract workers to their firms

To retain workers, employers raise wages, thereby increasing workers’ buying power (i.e. aggregate demand)

The increase in aggregate demand raises inflation

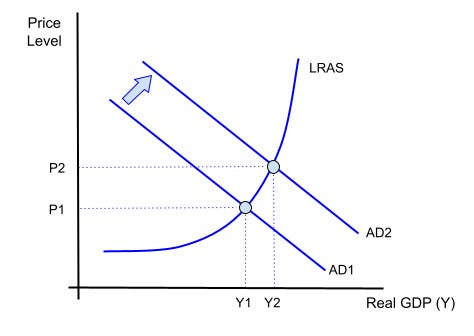

This process can be visualized like so:

The LRAS is the long-run aggregate supply, which represents the real GDP level that an economy can produce in the long run when using its available resources to the max. The graph shows an increase in aggregate demand from AD1 to AD2, which then increases real GDP from Y1 to Y2. This allows firms to employ more workers, but the increase in aggregate demand has inflationary effects, as reflected in the graph’s corresponding Phillips curve:

Lower unemployment, higher inflation. That’s the basic logic behind the Phillips curve. But obviously, an economy’s aggregate demand and supply constantly shift, and this is where things get a little hairy as we’ll have to once more turn to the short vs long-run distinction in the Phillips curve. For now, however, all you have to know is that the LRPC is the natural rate of unemployment, which is the labor market’s equilibrium point. There exists no shortage or surpluses of workers, and hence no upward or downward pressure on wages. Perhaps more importantly, the natural rate of unemployment isn’t affected by inflation (which is why it’s sometimes called the non-accelerating inflation rate of unemployment, or NAIRU).

With that in mind, this means that the intersection between the SRPC and LRPC is the economy’s full employment, where nearly all able-workers are employed. Keep in mind that this doesn’t suggest the complete absence of joblessness, as some will always exist in the form of frictional unemployment (workers shifting between jobs) and structural unemployment (basically a mismatch between the skills workers have and the skills employers demand. This is often attributed to rapid technological advancements).

Each point makes sense given the characteristics of the scenarios they represent. Recessions entail high unemployment and low inflation (sometimes even deflation), inflation often reduces unemployment (again, in the short-run), and full employment is when the unemployment rate meets the natural rate of unemployment, or the LRPC.

The Phillips curve itself can also shift along with the aggregate supply curves. Remember, any shifts in the aggregate supply or demand curves will result in price changes and thus, shifts in inflation and unemployment. The difference between the 2 is that if aggregate supply shifts to the left, creating stagflation (higher price level but lower economic output), the entire Phillips curve will shift to the right, creating higher inflation and higher unemployment. This is because stagflation is an entirely new situation so to speak, one that can’t be reproduced by moving up or down on the Phillips curve; the whole thing needs to move.

The red dot represents stagflation (higher inflation + lower economic output), the yellow dot full employment (aggregate demand and supply at equilibrium), and the green dot represents economic growth (greater economic output at lower prices). When mapping out these examples onto the Phillips curve, here’s what they’d look like:

The stagflation results in higher unemployment and higher inflation, whereas the economic growth reduces the unemployment rate. Equilibrium, on the other hand, stays at the same position.

But what about the long-run?

The question you’ve all been waiting for: why won’t economists use the Phillips curve for the long-run? Say inflation is 5% – this means that in addition to wages rising 5%, so are goods and services. In the short-run, yes, unemployment may decrease as people see their wage increase but aren’t yet feeling the general price increases (a phenomenon called the money illusion). This makes them susceptible to taking on any wage that they think is benefiting them, when in fact it may not even keep up with inflation.

But once all prices have risen and ordinary workers feel the effects of inflation, they realize that they’re essentially being ripped off with their current wages. As such, they demand higher wages to compensate for the inflation, thereby creating unemployment. This “natural rate of unemployment” isn’t affected by inflation in the long-run and is instead determined by other factors such as demographics, technology, and the labor market structure.

That’s why the long-run Phillips curve is literally a straight vertical line at the natural rate of unemployment; any attempt to change unemployment through monetary policy would simply change inflation without any long-run effect in employment. Eventually, things return to their equilibrium.

Econ IRL

When people think of the effects of minimum wage, their minds often jump to employment numbers or the prices of goods. Seldom do they immediately think of crime rates. This week’s paper however, examines that exact relationship; the minimum wage and crime.

The authors first and foremost note that improving low-skilled labor market conditions is likely more cost-effective than expanding police personnel in decreasing overall crime rates. Having said that, the authors look at what raising the minimum wage – a policy that, through higher wages, could theoretically attract low-skilled workers and reduce crime – does to the area’s local crime rates.

Using data from the 1998–2016 Uniform Crime Reports, they find that a 1 percent increase in the minimum wage is associated with a 0.2 percent increase in property crime arrests among 16-to-24-year-olds. The leading suspect for this increase? Simple: job losses caused by min wage increases

‘Till next time,

SoBasically