Trade policy, as we have seen in our previous article, is an important area for economists to study and, perhaps more importantly, for legislators to deliberate over. But said deliberation requires an understanding of how effective a proposed trade agreement is at furthering the country’s economic interests. That way, resources won’t be wasted on subpar deals when there are in fact superior alternatives available. That raises the question: how are we supposed to predict the impacts of a given trade policy being implemented? One way to do that is the gravity model and yes, it actually does have some overlap with physics.

The Basics

The gravity model seeks to predict bilateral trade flows (the flow of goods between 2 trading nations) via the economic size of and the distance between the 2 nations in question. The theory has its origins Ernst Georg Ravenstein’s theory on migration patterns from the 1880s, who postulated that the majority of migrants move a short distance and migrants who move longer distances tend to choose major sources of economic activity.

There were 2 main international trade models prior to the gravity model: the first was the Ricardian one, which emphasizes the importance of the distribution of technology in trade patterns, and the second was the Heckscher-Ohlin model that pointed to differences in factor endowments (the land, labor, capital, and entrepreneurship that a country possesses and can use for producing stuff) among countries. No one thought to pay much attention to the actual size of an economy.

Then in the early 50s, economists Walter Isard and Merton Peck expanded Ravenstein’s laws to international trade and arrived at similar conclusions, namely that:

Larger countries will attract more trade

Trade between 2 countries will fall with the geographic distance between them

Our physics readers should now be nodding their heads in familiarity. The theoretical similarities between the gravity model of trade and Newton’s law of gravity are indeed striking. Quoting directly from his Philosophiæ Naturalis Principia Mathematica:

Every particle of matter in the universe attracts every other particle with a force that is directly proportional to the product of the masses of the particles and inversely proportional to the square of the distance between them.

In other words, the gravity between 2 bodies depends on their masses and the distance between them. Likewise, the trade between 2 countries also depends on the distance between them but also their relative economic sizes. Even the equations kind of correspond with each other. Here’s Newton’s:

With Fg being the gravitational force, G the gravitational constant, m1 and m2 the 2 masses of the bodies, and r the distance between them. Isard’s and Peck’s basic model can be written like so:

In this formula, F represents the trade flow, G is a constant variable, D is the distance between the 2 countries and M stands for the economic size, usually in GDP, of the countries in question. Do keep in mind, however, that this equation really is the basic version of the gravity model and assumes ceteris paribus. More sophisticated versions account for things like culture (the US and Ireland, for example, engage in a lot more trade than the rudimentary model would suggest, partly because of the shared language between them) or the trade policies between countries (the above equation underestimates the trade between the US, Canada and Mexico because it doesn’t account for the existence of USMCA; the United States–Mexico–Canada Agreement).

Why It Works

What’s curious about the gravity model is that it has its roots in a field – physics – that’s very dissimilar to economics, and it’s not often that incorporating a theory from a completely different area of study into your own works so well. But why does the gravity model manage to paint an intriguingly accurate picture of international trade?

Well let’s start with a fairly obvious fact: the trade between 2 countries tends to fall with distance. The transportation of goods from point A to point B costs money, which increases the further the 2 points are from each other. Shipping cargo from the US to Canada is much cheaper than shipping that exact same cargo from the US to China. But distance doesn’t even have to be taken literally. It could also refer to the firmness of any pre-existing relationships between a pair of countries - if 2 nations have been trading for decades then it’s going to be significantly easier for a firm to find a buyer or seller, draft up a deal, and actually follow it through.

Conversely, if 2 given countries have never traded anything with each other, then it’s up to some business in one of those countries to take up the task of surveying the other for buyers or sellers, reaching out to them for the first time, and hopefully get a deal going. Going through all of this costs resources, and it’s a price that few companies are willing to pay.

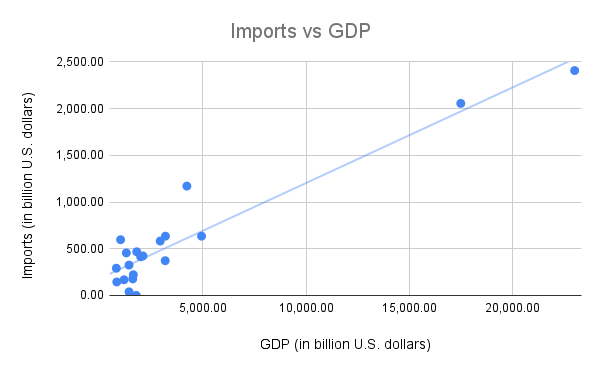

As for the second factor – economic size – this too isn’t an entirely puzzling phenomenon. Countries with large economies not only spend a lot on imports (see the graph below), but are also able to produce a variety of products given how advanced their manufacturing capabilities are. As such, revenue from smaller economies tends to gravitate (pun intended) towards these kinds of products, products that they otherwise would not have access to.

Criticisms

Like any economic theory, the gravity model of trade is not without criticism. Among the main concerns are doubts regarding being able to test the theory; the gravity model is indeed one of the most robust empirical findings in economics, but how do we know that said findings are causal rather than simply correlational? Patrick Minford of Cardiff University, the economist who originally raised thai point, contended that it’s possible that the relationship between an economy’s GDP and its trade volume could simply be the other way around, with the large trade volumes causing the large GDP.

Another objection that’s gained ground especially in more recent years is that the gravity model may be growing obsolete with the rise of intangible services being facilitated through the internet. Digital goods and services have virtually no transportation costs and thus render the gravity model as an inappropriate means of analyzing their trading patterns. While it’s certainly possible that, with the current trajectory of the internet dominating the global economy, gravitational ties may gradually loosen up, it goes without saying that transportation costs are here to stay.

Econ IRL

Discussions of the minimum wage almost always look at the policy’s potential impact on employment; the question of whether or not implementing the minimum wage results in increased joblessness seems to be the only one people are interested in. This week’s paper brings light to another potential consequence of such a policy: the rental housing market.

This is a particularly relevant question to ask since low-wage households, who are more likely to be tenants, are most affected by the minimum wage, and will therefore be most affected by the potential effects on rents. The researchers constructed a panel dataset consisting of ZIP code and its corresponding minimum wage, which is crucial seeing as how the minimum wage can vary wildly depending on where you live. The dataset also distinguishes between “workplace” and “residence” minimum wages, which basically describes the minimum wage of wherever the average employee works vs where they live (i.e. rent their home from).

The authors find that for every 10% increase in the workplace minimum wage, a 0.68% increase in rents follows, whereas a 10% increase in the residence minimum wage results in a 0.22% decline in rents. In addition to comparing the effects of residence and workplace minimum wage increases, the authors also wanted to assess the share of newly generated income by the minimum wage that is pocketed by landlords.Turns out it depends on whose minimum wage we’re dealing with here; 9.2 cents is pocketed for every dollar hike in the federal minimum wage, and 11 cents is pocketed for every dollar hike in the city minimum wage.

‘Till next time,

SoBasically