The Currency Markets

When people say "there's a market for everything," they're not messing around

We think of currencies such as the American dollar or the British pound sterling as the way people buy and sell goods and services. In other words, that money serves as an intermediary of sorts that lets the buyer acquire an item and the seller to be compensated for giving up that item. We don’t usually think of different currencies as being the actual goods in question or the “product” that buyers and sellers trade with one another. Welcome to the foreign exchange, or forex, market, - the global market for currencies.

A brief history

The modern forex market has its roots in the immediate aftermath of WW2, with the signing of the Bretton Woods Accord. Prior to this, countries would peg the value of their currencies to precious metals (think systems like the gold standard), not leaving much room for international currency trading. What Bretton Woods did was attempt to foster a more multinational approach to managing currencies (and with it, worldwide free trade), specifically through creating an efficient forex market.

With over 700 delegates representing 44 countries, the conference accomplished mainly 2 things:

Set up the US dollar as a sort of world currency unit, with other countries pegging their currencies to the USD by setting a specific exchange rate relative to the USD (i.e. 2 Japanese yen = 1 USD). The US government also made clear that they were going to link the dollar to gold at a rate of $35 per ounce, which would allow foreign governments and central banks to exchange dollars for gold. All this meant that the international system of payments revolved around the dollar, wherein all currencies were valued in relation to the dollar - America’s currency was now basically the world’s currency

Established the International Monetary Fund (IMF) and the World Bank. The purpose of the IMF was to ensure that other countries were following the rules with regards to international finance (countries had to, for example, request IMF approval if they wanted to change their currency’s exchange rate with the USD by more than 10%). The IMF also counselled countries on monetary policy and issued loans to nations if they incurred a balance of payments deficit (when a country imports more than it exports, meaning it must borrow money to pay for these outstanding imports). While the World Bank, on the other hand, also issues loans, the intended recipients are low to middle-income countries that could use the funds to develop their economies

As great as the Bretton Woods Agreement may have sounded, especially seeing as how it was implemented in a time when the world yearned for some sense of international allyship, the system didn’t last long. In 1971, US President Richard Nixon, worried that America’s supply of gold wouldn’t be able to keep up with the money supply, temporarily suspended the convertibility of the US dollar into gold until certain reforms (mostly ones that would help stabilize the US dollar; keep in mind that the American economy at the time had an inflation rate of above 5%) were made to the Bretton Woods system. These renovations never came to fruition, and so the inconvertibility of dollars to gold continued until 1973, when Bretton Woods was unofficially replaced with the currently-prevailing system of free-floating exchange rates, where the value of currencies are set by the forces of supply and demand within the forex markets.

How forex works

The market for currencies is perhaps one of the most secluded out there simply because it’s literally just central banks and other financial institutions swapping sums of money for a different kind of money. Despite receiving a fraction of the attention that the stock market does, trading volumes in the forex markets averaged around $6.6 trillion per day in 2019. For reference, the total annual trade volume of the stock market that same year was just over $61 trillion. Forex markets are open 24 hours a day from Monday to Friday and comprise mostly of central banks, private financial firms, and speculators.

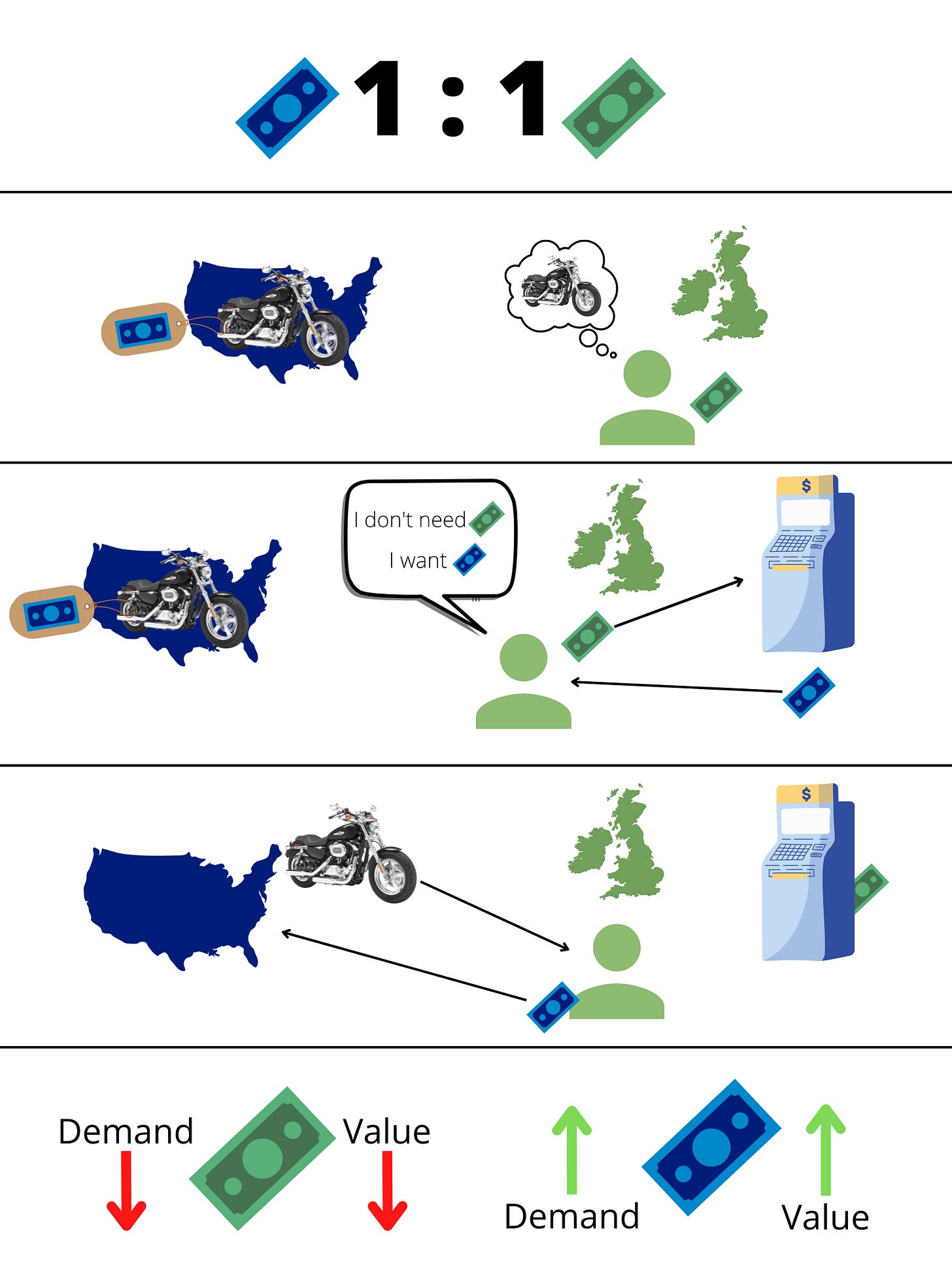

The important thing going forward is that in the forex markets, currencies themselves are goods being exchanged. So like apples, the price of the US dollar in another currency is determined by supply and demand. The “price” in this case is referred to as the exchange rate, which is essentially the current price of a given currency in terms of another currency. So if you’re in the UK, “buying” 1 USD will “cost” you roughly 0.82 British pounds (at the time of writing):

An increasing exchange rate indicates that more people are willing to “sell” their currency - so if 1 dollar suddenly brought you £0.4, this means that holders of the dollar want to give up the currency. But what do they want to give it up for? The pound in this case. That’s why you can now “buy” less pounds with each dollar - demand for it goes up, and the price follows. So instead of being able to buy £0.82 with $1, you now need roughly $2 to get your hands on £0.82, as a single dollar will yield you only £0.4.

So what does this mean in terms of the value for both currencies? Well, holders of the dollar no longer want that currency for whatever reason, which is another way of saying that the dollar's demand has decreased. A decreased demand, ceteris paribus, means that the currency depreciates (when an asset becomes less valuable). Conversely, because more people are demanding the British pound, the currency appreciates (when an asset becomes more valuable). Thus, the depreciation of one currency must necessarily mean the appreciation of another currency. But what actually impacts the exchange rate of a given currency? 3 key factors:

Interest rates/inflation

Perhaps the most intuitive of the 3; the rate at which a currency loses its purchasing power will impact how attractive that currency is to foreigners. Because inflation is in large part controlled by interest rates, these metrics are hence closely watched by forex traders. People who are looking to save their money will want a currency that doesn’t lose its value too quickly, so if America’s interbank lending rates rise higher relative to the UK (which is indicative that inflation in the US will slow), then British savers on the forex markets are going to convert their pounds into dollars.

This will result in 2 things: first, the higher supply of British pounds relative to American dollars, since the UK’s interest rates are lower than America’s, thereby expanding the UK’s money supply. Secondly, the increased demand for American dollars, as that’s now the currency that loses its value less overtime, and so people will want to hold onto dollars in order to preserve their wealth. Shorter supply + higher demand = an appreciated American dollar and a depreciated British pound.

International trade

Now here is where we step into the realm of actual products that people engage with on a regular basis; products such as Aston Martin cars from the UK or Harley-Davidson motorcycles from the US. The popularity of the cars among American consumers and of the bikes from British consumers affects the demand for the dollar and the pound, even though vehicles and currencies are technically different markets.

In order for British importers to acquire American Harley-Davidson motorcycles, they need to convert their pounds into dollars - they want to get rid of British pounds and get their hands on American dollars. An increased demand for the dollar, the dollar hence appreciates in value.

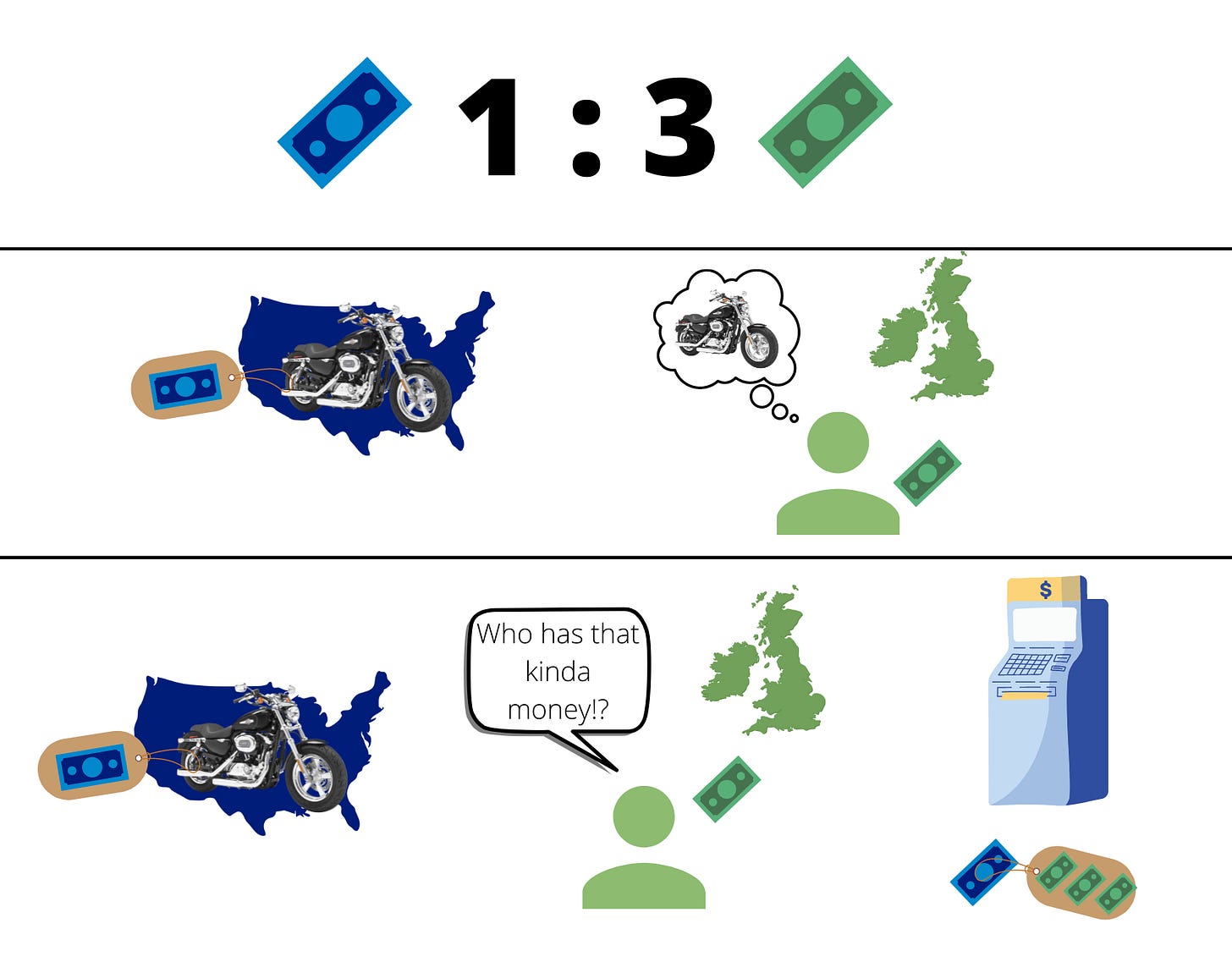

The problem with continuing down this route for too long, however, is that as the currency appreciates, the country’s products become more expensive. If the conversion ratio from USD to GBP starts out as 1 to 1, but then the USD increases in value such that you need £3 to get a dollar, British citizens now have to pay triple the amount in their currency for a $1 American product. Overtime, American products will decline in popularity as they’ve simply become too expensive, at least too much for the UK consumer base to put up with.

In order to avoid this dilemma, American manufacturers could simply price their goods to the UK population in the British pound. Doing so keeps the exchange rates largely intact, which would protect manufacturers from an overly-appreciated dollar.

Relative income

This might be the most seemingly unrelated factor. How can the average income of a country affect the exchange rate of that country’s currency? It all boils down to what people decide to purchase when they have more money to spend relative to another country. Say that the average American income surpasses the average British income, giving Americans more money to spend on goods both foreign and domestic. The richer you are, the greater your propensity is towards importing products, as you can now pay the extra cost for shipping, the product’s higher quality, etc.

And as we’ve just established, importing goods from another country means you’re giving up your national currency in favor of the respective foreign currency, depreciating the value of the latter and appreciating the value of the former. Thus, as odd as it seems, the wealthier a nation becomes, the less valuable its currency.

Econ IRL

There’s an American television game show called "The Price is Right" in which 3 contestants take turns to spin a wheel that contains the multiples of 5 up to 100, and the aim is to get closest to 100 without going over (bonus points if you land on 100). The caveat is that after spinning the wheel once, the next contestant must decide whether to spin the wheel another time. If they spin once, then whatever number they got is their score but if they spend a 2nd time, the score is the sum of both numbers.

A game theorist would call this a sequential game, meaning the players make decisions following a certain predefined order and that at least some players can observe the moves of players who preceded them. With this, we can find the Nash equilibria for all the game’s “subgames” (a certain part of the game where the player’s initial choice is the only information they have regarding the game). So that’s what the authors of this week’s paper did.

Making the optimal choice means you need to weigh the possibility of getting a better competitive score and/or a shot at the bonus prize vs the chance of being eliminated. Here are the final results

- Player 1: spin if score is 65 or lower, stop if score is 70 or lower

- Player 2: spin if score is lower than player 1's score or if their score beats player 1's score but is 55 or lower, stop if score beats player 1 and is 60 or higher

- Player 3: spin if their score is worst than the best previous score, stop if it's better

‘Till next time,

SoBasically

Good article, well done