The Business Cycle

What goes up must come down

What is the business cycle?

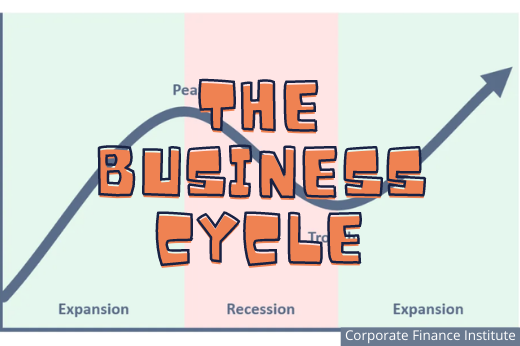

Why do economies grow and contract? How is it that depressions occur seemingly out of nowhere? Are markets becoming more unstable? These are the questions economists constantly ask themselves when studying the business cycle. Sometimes called the economic cycle or the trade cycle, the business cycle is GDP fluctuations despite there being overall, long-term economic growth.

The ups are characterized with high growth and low unemployment whereas the downs are generally defined by low/stagnant growth and high unemployment. All modern industrial economies experience these swings in economic performance over time.

So...what causes these economic cycles?

See that’s the thing: we don’t know.

For a long time, classical economics either denied their existence or blamed them on obvious external factors such as a storm wiping out farm’s crops (which would increase the price of crops). Later, French economist Jean Charles Léonard de Sismondi challenged these ideas with his book Nouveaux Principes d'économie politique and by citing the Panic of 1825 - a stock market crash in the Bank of England which didn’t initially have any clear reason as to why it occurred.

Robert Owen, who was greatly influenced by Sismondi’s writings, later identified the cause of these booms and busts as production and consumption not syncing with one another, thus leading to periods of overproduction and underconsumption. This theory was and still is rejected by most academia, however Owen’s underconsumption part later influenced other schools of thought.

In 1860, a more sophisticated model was put together. French economist Clément Juglar argued economic cycles were roughly 7-11 years long and could be represented by his very own Juglar cycle:

Expansion, high growth, low unemployment, and increasing prices

Crisis, the turning point when things get bad real fast, often with multiple bankruptcies occurring at once and a stock market crash

Recession, slowdown in economic activity with low/stagnant growth and declining prices

Recovery, the other turning point of a business cycle in which things start improving

While most economists may accept this analysis, it still doesn’t really answer the original question: why do these economic ups and downs keep happening? What triggers them? How can we predict when another one is coming?

Mainstream economics views business cycles as random and unpredictable phases - bit of an underwhelming explanation. In 1927, Eugen Slutzky discovered that coming up with random numbers could generate patterns similar to that which we see in business cycles, causing economists to move away from viewing business cycles as something that needed to be explained and addressed accordingly. So what appears to be a clearly defined cause-and-effect theory can actually be explained as just random spontaneous events. Thus business cycles are essentially random shocks that average out over time.

Of course, not all economists agree. Keynesians - people who follow the ideas of John Maynard Keynes - argue fluctuations in aggregate demand (total amount of demand for all finished goods and services produced in an economy) is the primary force driving these booms and busts. Low aggregate demand means lowered economic growth and increased aggregate demand gives more economic growth.

There’s a lot more to it than that and many other theories from different schools of thought, but let’s not get into that right now.

What can we do about the busts?

Periods of economic stagnation can really suck - job losses, businesses having to close down, people building up debt. Recessions have also been correlated with worsening crime rates, suicides, and mental health issues. As such, there is often significant political pressure for the government to do something about it.

This is a big area where Keynesian ideas are considered the mainstream ones. If we can correlate booms and busts with aggregate demand levels, then that means to increase economic growth during a bust, we must boost aggregate demand. According to Keynesianism, the government has to do just that. Stimulus packages, lowering interest rates for loans, employing people in the public sector - anything to put money in people’s pockets which can then be spent into the economy.

This has been the standard guide for addressing busts since the 1940s, following the Keynesian revolution. But do these tactics really work? We certainly haven’t been recession-free since WW2. So the question has to be asked: are these recovery policies really fixing anything, or do they merely delay the next bust?