The Bond Market

The name is Bond, T-Bond

In any instance of a loan being issued, there are 2 parties involved: the lender and the borrower. To the lender, the loan is an asset; they will hopefully make money from the loan in the form of interest. To the borrower, the loan is a liability, something that they have to pay back in a certain amount of time. The lender, being the owner of the loan asset, may want to sell this asset to someone else for whatever reason. This isn’t easy to do with the loans that people usually take from the bank, but is in fact the sole purpose of another type of security: bonds.

Bonds are, put simply, highly transferable loans in that the ownership is bought and sold between investors, businesses, and governments. When someone buys a bond, they are lending money to bond sellers/issuers (the borrowers) with the expectation of profit. “Issuing” a bond is essentially declaring the need or want for money, whereas buying a bond is declaring a willingness to lend money.

Although loans and bonds are similar in their core purposes, there are some bond-specific characteristics and terms to be noted. A bond’s face value is how much the bond is worth at its maturity date, that is, when the loan is to be paid back in full. So if I buy a 10-year bond at an issue price of $10,000 with a coupon rate (bond version of interest rate) of 5% per year, that means the face value will be $15,000. Coupon dates are when a bond issuer is to make interest payments, often occurring semiannually.

Thus far, bonds sound just like regular loans but with relabeled vocabulary. But bond owners, unlike loan holders, don’t usually hold onto this asset until maturity - they sell it on what’s called the secondary market, where previously issued financial instruments are bought and sold. Bond prices in the secondary market can be extremely volatile, just like stock prices, and are significantly influenced by interest rates in addition to the actual bond characteristics. Let’s turn to our example from above: an issue price of $10,000, a 5%/year coupon rate, and a maturity of 10 years. Say that the current interest rates for government bonds (bonds issued by the government) are also 5%.

This separates the primary bond market (the one where bonds are first issued) into 2 categories that investors can choose from: ones issued by the government and ones issued by the private sector. But with both bonds set at the same interest rates, a bond buyer would be indifferent to purchasing one from the government or the private market, since both assets offer the same returns, namely $5,000 in interest. But if the government drops the bond interest rates to 3%, the returns for that bond have also decreased to $3,000, which ends up making the private bond more attractive - the demand for it increases and thus, as does the price.

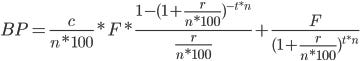

Likewise, if the government sets their bond interest rates to say, 20%, that’s going to increase the price for government bonds given their higher return on investment compared to private bonds. There is, in fact, a formula we can use to calculate the exact price of these bonds with the given information.

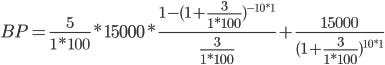

F is face value, c is coupon rate, n is coupon rate frequency (so 1 meaning there’s a coupon date each year, 2 meaning there’s 2 coupon dates each year, 4 meaning there’s 4 coupon dates each year, etc), r is the interest rate of the other kind of bond (either the private or government bond, depending on which price we’re looking for) and t is the number of years until maturity. So if we want to figure out the price of our government bond before the interest rate decreases:

Put simply, because both the private and government bond coupon rates are the exact same, their prices will also be identical. But if the government bond has a slightly lower coupon rate:

The coupon rate dropped as did the bond price - the government bond is worth less than the private bond, which is now priced at:

The private bond’s coupon rate didn’t change, and so because it’s now higher than that of the government bond’s, the price has now been raised. And that is how bonds are priced: through a symphonious process of the private and public sector constantly checking in on each other’s interest rates and adjusting their prices accordingly.

Econ IRL

If you read our stock market article, you’ll know that the prices are based largely on what people think the stock will do. In other words, investor prospects determine the prices. These prospects can be pessimistic, optimistic or, according to this week’s paper, over-optimistic. The authors found that unrealistically positive expectations for an economy’s growth being published can actually result in economic contractions a few years later.

Using what’s called an instrumental variable approach - a tool that estimates casual relationships when controlled experiments aren’t feasible - the researchers analyzed IMF forecasts to determine if there was a link between overly-optimistic projections and a subsequent slowdown in growth and sure enough, there was.

‘Till next time,

SoBasically