With the 2023 banking crisis seemingly cooling off, we thought it would be a good idea to do a comprehensive overview of how banks are structured and operate in the modern economy. Yes, we already have an article on this very topic from way back when, but we’re going to go a bit deeper this time so you can hopefully better interpret the recent wave of bank failures. And what better way to do that than by comparing the 2 competing systems of banking?

Fractional reserve banking

This is pretty much the internationally-adopted system of banking, and the system that you interact with almost everyday. In fact, you probably already have a rough idea of how these banks function, but just to quickly review: fundamentally, banks are a safe place for depositors to store money. Instead of hiding their cash under a mattress, people can safely deposit those funds in the bank and not only have access to them, but they’ll also get paid for storing their money through interest.

And while this money may be the depositor’s assets (since it’s literally their money), it’s the bank’s liabilities – it’s money that they have to pay interest on to depositors. The only reason the bank even has that cash is because other people are entrusting their savings with them. At the end of the day, however, banks are businesses and are thus looking to make profit. This is where loans come in: by charging interest on the loans (which are made up of depositor money), banks turn their liabilities into assets so to speak.

Or at least, most of their assets. If a bank were to receive $1000 in deposits and lend out the same amount, they’re basically sabotaging themselves. Because remember, depositors are entitled to that money too, and can demand to withdraw it anytime they please. That’s why required reserves exist; by keeping aside a certain percentage of the received deposits, the bank can, with some assurance, pay off the withdrawals. And so, banks will keep some deposits and lend out the rest.

That’s the essence of fractional reserve banking; keeping a fraction of deposits and lending out the rest.

The financials

Here’s how we’d model a standard fractional reserve bank through balance sheets and an income statement:

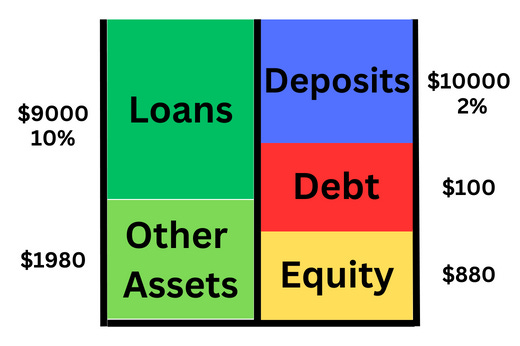

Here we have a typical bank balance sheet. On the left are the bank’s assets, namely loans and other items such as government bonds, properties, and liquid cash. On the right are the bank’s liabilities such as debt on loans, equity owed to shareholders (since equity represents what the shareholders contributed to the bank’s funds), and of course, deposits. During the bank’s first year of operations, things might look something like this:

Here’s the situation. The bank is making 10% off the $9000 in loans, and paying their depositors 2% of their $10000 in savings. The interest income is thus $900, and the interest expense is $200. Let’s assume $100 in other expenses (salaries, building maintenance, etc), $400 in shareholder’s equity, and a 20% tax rate. With that information, we can come up with the income statement:

During their first year of operation, the bank made $480 – cash that can be added to their “Other Assets.” But that’s not what bank executives would necessarily pay attention to. Being a business first and foremost, the goal is to maximize shareholder equity. After all, it’s the shareholders that chose to invest in the bank and provide it capital, creating a fiduciary expectation for the bank to act in the investors’ best interests. Here’s the updated balance sheet:

And voila, shareholder’s equity has more than doubled over the course of 12 months. Under business-as-usual situations, this is more or less a fractional reserve bank’s yearly routine.

Full reserve banking

So if fractional reserve banks keep a fraction of customer deposits, it follows that full reserve banks keep all deposits on reserve. If I put $1000 in a full reserve bank account, that money isn’t being lent anywhere – I can access it whenever I want. Now this raises the obvious problem of where a bank’s income would come from. Fractional reserve banks earn money by lending out most deposits and charging interest on them. Sure this carries the inherent risk of the bank not being able to keep up with all their customers’ withdrawals, but at the end of the day it fulfills a crucial function of banks, namely to transform unproductive funds into productive investments by connecting savers and borrowers.

So, how do full reserve banks address this problem? Through a neat little system called time deposits. This is a kind of deposit wherein customers agree to leave their money in the account for a set period of time and in exchange for doing so (and thereby forgoing present consumption), the customers receive a higher interest rate than they would on a fractional reserve bank account. This arrangement assumes that because customers won’t need every penny of their deposits on-demand all the time (which is usually true), they’d be willing to effectively “lend” extra money to the bank in exchange for interest. Then, the bank can lend out that “borrowed money” and earn interest.

Of course, if a full reserve bank chose to lend out borrowed money from a customer, they would have to make sure that not only their loan is fully paid in time, but that the interest they receive is enough to pay the interest fees they owe to the customer. This can quickly turn into a risky undertaking, which is why full reserve banks rely more on higher banking fees rather than loans from interest rates to make money.

On that note, a full reserve bank’s balance sheet would be probably look something like this:

Notice how there’s no “debt” in the sense of owing money to lenders. Remember, full reserve banks cannot lend any more money than they have in reserves, forcing them to rely on banking fees charged to customers (hence why it takes up such a large space on the assets side). Consequently, there’s literally no need to rely on loans to fund its operations.

One key difference between full and fractional reserve banking is their role in money creation. Under the fractional reserve banks, money is created every time a loan is given out and deposited into a savings account. A bank receives $100 in deposits, keeps $10 and lends the rest. That $90 ends up in another account, of which $9 is kept and $81 is lent out. If this process continues until the end, nearly $1000 will be created not in physical dollar bills, but in deposits.

By contrast, if a full reserve bank lends $100 from time deposits to another bank, it’s merely transferring that money from the depositor’s account to the borrower’s account. The total amount of money hasn’t changed because the depositor has agreed to temporarily forgo ownership of that money so to speak, thereby allowing the full reserve bank to lend it out.

Econ IRL

Zoning laws, which regulate how particular plots of land may be used (i.e. residential, commercial, industrial, etc), are probably the most common urban planning methods in the developed world. Despite their widespread usage, their effects on housing affordability is a hotly-debated topic, especially as many developed economies are struggling to keep housing prices at reasonable levels.

The ultimate question here is how do zoning laws affect the housing market? Using data of zoning reforms in hundreds of US cities, this week’s paper studies the effects of changing zoning laws on housing affordability. The authors find that loosening restrictions (“upzoning”) results in an increase in housing supply (i.e. more construction). However, it’s unclear as to whether this is the case the other way around: tightening restrictions (“downzoning”) may not necessarily reduce construction, the authors argue, but the correlation between downzoning and increased rents is clear nonetheless.

‘Till next time,

SoBasically