Derivatives

Where things get serious

The 2 types of securities that we have thus far covered, namely equity (stocks) and debt (bonds and loans), are fairly layman compared to the third type: derivatives. And no, calm down, this has nothing to do with math functions. Although these are probably the financial instruments you’re least familiar with, don’t underestimate their relevance: their market is often estimated at over $1 quadrillion, with some analysts estimating it to be more than 10 times that of the world’s GDP. So, exactly what are these things?

Derivatives are assets whose value is derived from the performance of some other underlying entity. The definition speaks to the literal term itself: a deriv-ative derives value from something else. These underlying assets can be basically anything, from stocks, indexes, commodities, other derivatives, etc. This is done with 2 parties putting together a contract and essentially betting on the change in price of the underlying asset, and as the value of the underlying asset changes, the value of the derivative changes accordingly.

Here’s an example: say you sign a contract agreeing to buy a car from a friend for $1000 in 6 months time if and only if they promise to sell it to you and only you. The two of you sign a contract and agree to meet each other in 6 months. A few months pass, and the company that makes this car jacks their prices to $1500, and so your friend has actually found someone willing to pay $1300 for that car. Unfortunately for them, they’re stuck with you and your 1k as they signed a contract. Except, no, they aren't stuck with you.

What you can do is sell your side of the contract, that is, the side which agrees to pay $1000, for $300 to whoever’s willing to pay $1300 for the car ($1300 - $1000 = $300). This means that whoever buys your side of the contract now has an obligation to buy your friend’s car for $1000. Now while this contract buyer may be getting the car for only $1000, he actually, in a sense, paid $1300 for it; $300 for the contract side and $1000 for the actual car.

This kind of derivative is called a forward contract or simply forward, where parties agree to buy or sell something at a specified price on a future date. There are a few other kinds of derivatives out there:

Futures

Technically, this is a type of forward contract but it deserves its own category. These are simply prewritten, standardized contracts sitting on shelves waiting to be sold. Instead of having to write forward after forward, you can simply copy and paste a few general details and sell it as a future: 50 Apple shares in a month for $180 each. (Please note that we are NOT giving financial advice and SoBasically isn’t responsible for any money lost to messing around with these things).

Unlike forwards, which are private and customizable, futures are more of a “take it or leave it” situation, the price of which changes daily until maturity.

Put options

These are basically the same as futures in that it’s a contract between 2 parties agreeing to trade underlying assets at a predetermined date and price. The catch, however, is that the option holder has the right, not the obligation, to sell the underlying asset at maturity. This is why they’re called options - buying or selling the underlying assets are optional.

Say you purchase a put option from a broker, one that will give you the right to sell 50 Apple shares at $180 each in a month. Right off the bat, even if you do fulfill your end of the contract, a premium must be paid when you purchase the option. The reason is because the very possibility of you ignoring the contract is a big risk on the broker’s behalf, and so they would want that risk compensated.

In this arrangment, the broker would at least get something out of the deal regardless if you decide to exercise your right to sell the shares.

Call options

The reverse of put options; this time the buyer has the right, not an obligation, to buy an agreed underlying asset.

What all these options (pun intended) have in common, they’re all essentially zero-sum games. How? If your friend signs the forward and sells the car to you for $1000 in a market environment where that same car could be sold for $1300, he has in effect lost $300 whereas you saved $300. Heck, you could even sell that car for $1300 and make that profit (this is usually what happens with futures).

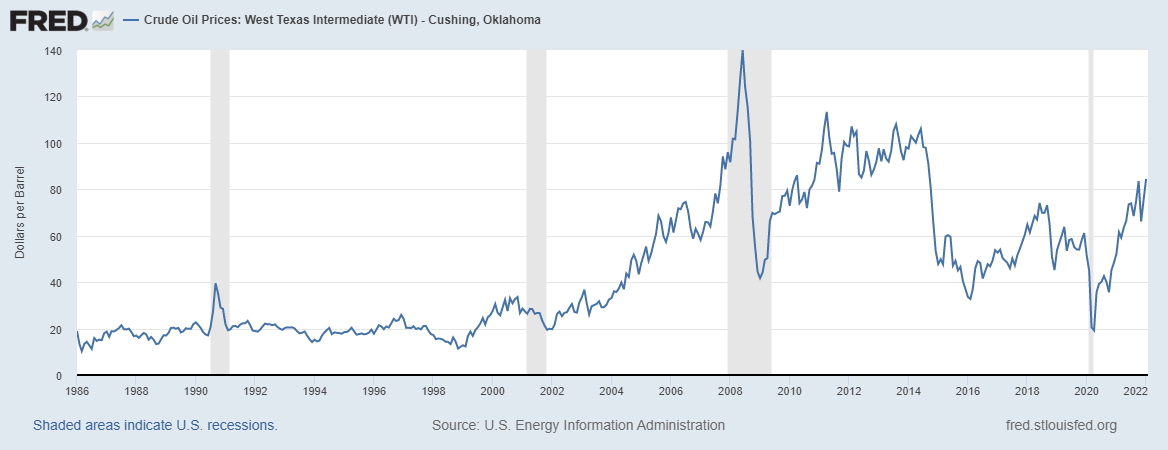

But why do people even buy derivatives in the first place as opposed to just, you know, buying the asset itself? Asides from being able to buy or sell stuff lower or higher than the market price, a lot of assets, such as oil, have some pretty unpredictable prices:

For companies that heavily rely on oil, such as airlines, it’s easier for them to plan their costs ahead of time instead of being at the mercy of the commodity’s volatility. Hence, they simply lock in a price today for oil they’ll need in the future through forward contracts and then leave it be.

Swaps

As the name suggests, this is an agreement where 2 parties exchange payments for a certain period of time. Technically what’s being traded can be almost anything, but most swaps involve cash flows. Now selling someone the obligation or right to buy something at a set price might make sense, but exactly how can one swap streams of cash? Say we have 2 borrowers: Bob who pays a floating interest rate (meaning the interest rate isn’t fixed over the mortgage’s lifetime) and Susan who pays a fixed interest rate. Bob thinks that interest rates are gonna go up in the near future, whereas Susan thinks the opposite. With this, they both agree on a notional principal amount (the amount of initial that doesn’t change regardless of the type of interest rate, that is, the initial amount of money lent) and a maturity date when they’ll take care of each other’s payment obligations.

So in effect, Bob is paying Susan a fixed rate while Susan is paying the floating rate to Bob. From here we can see how, depending on where interest rates go, this might favor either of the swappers. If Bob’s prediction is correct, meaning if interest rates do go up, then he profits and Susan makes a loss; the variable interest rate that Bob receives from Susan exceeds the fixed rate he has to pay to her, meaning he gets to pocket the difference. Susan, on the other hand, is giving Bob more money than she’s receiving from him.

But let’s switch the scenario: Susan is correct and floating interest rates decrease and end up going below the fixed interest. In this case, she has to pay Bob less money (the floating interest) than Bob gives her in the form of the fixed interest rate. Keep in mind, however, that normally with interest rate swaps (the kind of swap this example depicts), the payments are not directly exchanged but rather both pirates agree to do so through a financial intermediary such as a bank, who charges a small percentage of the money as compensation for connecting the swappers.

But what the Bob-Susan scenario illustrates is really the whole purpose of not just swaps but derivatives as a whole: hedging. This is a fancy word for offsetting risks and it allows different kinds of investments to flow towards those with the respective tolerance for risk. WallStreetBets users, for example, are probably looking for a little more thrill than someone who’s simply putting their savings into the S&P 500 to help with retirement. There are plenty of other kinds of swaps worth going over, not necessarily in this article however.

Econ IRL:

Humans, being social creatures, innately care about, to some degree, how others perceive them. As such, it can be reasonably inferred that a person’s behavior being recognized by others can influence their decisions (think initiatives such as “employee of the month”). With that point in mind, this week’s paper asks the following question: is social recognition an economic gain or drain? To answer this, the self-esteem gains that come with being recognized would need to be quantified and compared with the losses from shame that everyone else experiences for not being recognized.

The researchers conducted a field experiment in the YMCA with a “Grow & Thrive” program that encourages members to attend their local YMCA more often by having an anonymous donor give $2 to the YMCA each day that an individual attended. The twist was that participants would be randomly assigned to the “social recognition program,” (SRP) which would publicize each participant’s attendance and donations.

3 main results are documented. Firstly, social recognition increased YMCA attendance by 17-23%. Secondly, how much individuals are willing to pay for social recognition increases with their potential for future attendance (so -$1.70 for 0 attendances and $2.61 for 23 or more attendances). Thirdly, despite the attendance increase, social recognition still ended up being a net loss. How? The prospect of social recognition ends up crowding out gym-goers who hit the gym regardless of whether or not they’re recognized for doing so.

‘Till next time,

SoBasically